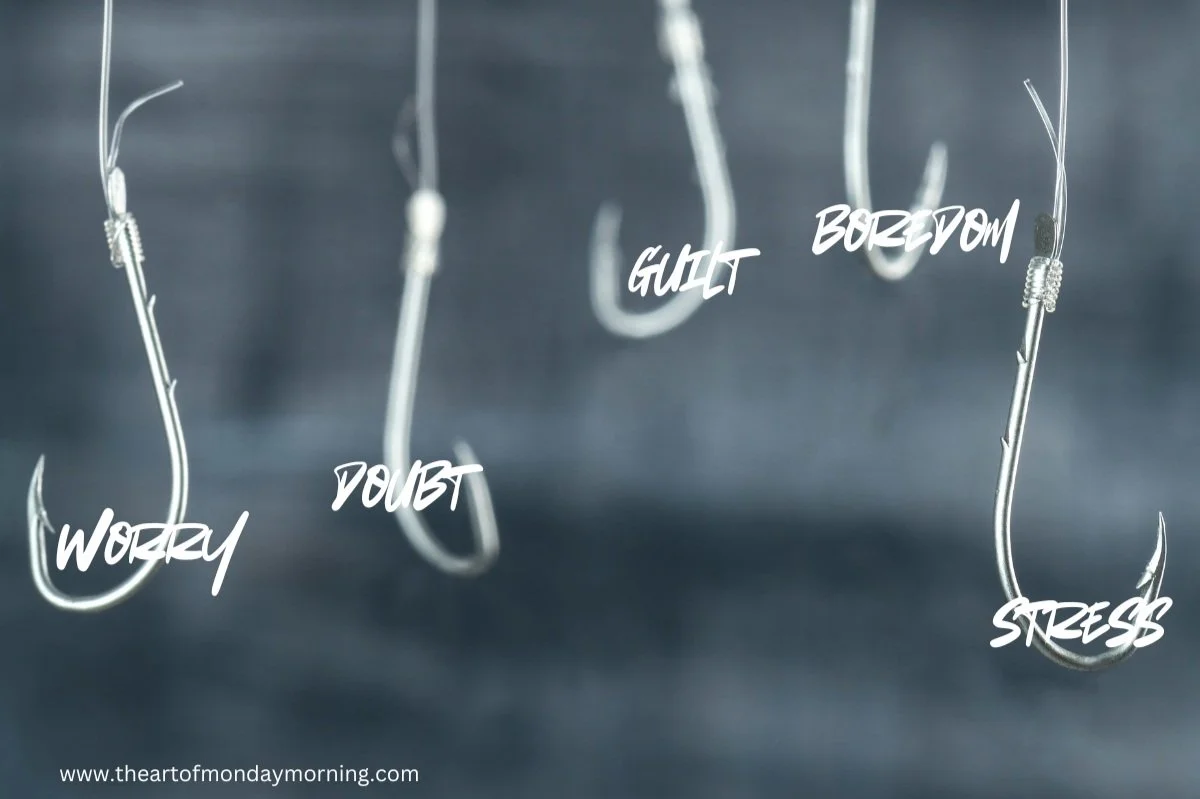

Fish Hooks Everywhere!

Meditation is a practice of focus—it’s building the capacity to focus my mind on what I choose to focus it upon, and by extension, to know when I’m not.

There is no “wrong side of the bed”

My actions are driven by my emotions, and my emotions are driven by my thoughts—both those that are conscious, and those that are unconscious. When I “wake up on the wrong side of the bed”, there absolutely is something going on in my mind that’s driving my sour mood, I may just not be aware of what it is.

My problem, though, is that as long as I’m not aware of what might be swimming around up there, I’m at its mercy. Like a big fish hook, it’ll grab my cheek and pull my mood (and the skill of my actions) wherever it wants to go: Maybe I’ll cancel a meeting I’ll regret later. Maybe I’ll snap at a customer, colleague, or boss (or someone I love). Maybe I’ll let up on something I’ll wish I had leaned into afterward.

“It’s not about the number of hours you practice, it’s about the number of hours your mind is present during the practice.”

Meditation is often thought of as a practice for relaxation, and while it certainly can be that, it was traditionally developed to be a skill of concentration—a capacity to focus my mind on what I choose to focus it upon, and by extension, to know when I’m not.

When meditation teacher, George Mumford, worked with Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant, this was the critical objective, and it’s easy to see why. Given the noise of the crowd, the pressure of the game, the value of the contracts and endorsements, and the ridiculousness of the tabloids (not to mention the five other highly-skilled huge guys desperately trying to stop them), their ability to focus on the ball, the action of the court, and the net was paramount to their ability to act and win.

“If you want to understand your mind, observe it.”

Seeing What’s Up There (Or, “Meditation 101”)

One needs only to have a peek at one’s own mind to see how noisy it can be, and how those noises can turn into distractions, obstacles, and worse. While I’d like to think that a blog post can’t touch the truly transcendent experience of me teaching it in person (insert wink here), the structure of the practice is simple enough to experiment with:

Be natural

Position yourself in a way that feels most easy and natural to you. There is no need to sit criss-cross-applesauce or twist your legs around like a pretzel. Want to sit? Sit. Want to lie down? Lie down.

Settle

Take a few deep breaths and allow yourself to settle and relax on the out breath. Hang out for a minute. Relax.

Choose a home base

Draw your attention to something that is naturally easy to focus on, such as:

The feeling of breathing (try not to think about breathing—just feel it)

The feeling of your own body on your seat

The sounds in the room (listen to them like someone is whispering a secret)

Allow your mind to do what minds do

Again, meditation is not about “not having any thoughts”, but about noticing what is there and directing our attention to what we choose to focus it upon. Give yourself space to see what’s there; to let your brain “brain.” There may be a temptation to follow the thought (or fix something), but as best as you can, allow yourself to just watch (you can dig in and fix stuff later, for now, just watch).

Notice and let go

When you notice that your attention is no longer on your “home base”, gently label where it went (e.g., “thought”, “sensation”, “memory”, “worry”, “song”), and then let the thought go by simply returning your attention back to your home base. Don’t worry if you get caught—that’s just what brains do, so go easy on yourself.

Begin again

Continue in this way for as long as it feels natural:

10 minutes? Great!

20 minutes? Way to go!

3 minutes? Awesome!

Like learning a language or an instrument, it’s more about consistency than it is about marathon meditation sessions once every six months. In this way, three minutes every day (or even three conscious breaths while the coffee is brewing) pay higher dividends than two hours one time per month.

Fish Hooks Everywhere!

Even a couple of minutes of this practice can be enlightening to say the least. A common description of the experience that is almost as old as the practice itself is “mad monkey mind”—dozens of thoughts everywhere, jumping all over the place, and any one of them a fish hook that could pull me towards it . . . if I let it.

This is the beauty of the experiment:

Can I see the fish hooks?

Can I swim by them without getting hooked?

And ultimately:

Can I swim towards the thoughts that I choose for myself?

We teach this every day in every kind of setting and with people from every kind of background. If you’re curious as to how we may be able to help you and/or your organization, please don’t hesitate to reach out to us.